Despite the

recent disappointing news about two fundamental programs seeking

Huntington’s disease treatments, significant drug-discovery initiatives proceed

steadily. They include two major clinical trials: KINECT-HD,

sponsored by Neurocrine Biosciences, and PROOF-HD, backed by Prilenia Therapeutics.

As reported

in Part I of this two-part series and a

previous article, Roche

announced that it had halted dosing in its historic Phase 3 gene silencing

clinical trial, followed by Wave Life Sciences’ revelation that a similar effort to

reduce the level of mutant huntingtin protein had fallen short.

In all

likelihood, these drug candidates – at least the current version of them – will

not become HD treatments.

However,

other candidates abound.

“Our pipeline is full of hope,” said George Yohrling, Ph.D., the

chief scientific officer for the Huntington’s Disease Society of America (HDSA), in a March 25 webinar

held to address the devastating clinical trial news. “Our pipeline is deep and

diverse.”

The HD research community “has not put all their eggs” in the

Roche “basket,” Dr. Yohrling explained. “We know what causes the disease, and

it’s the expansion of the huntingtin gene and the expression of this mutant

protein. There is a wide array of approaches that we are using to tackle that.

We’re hopeful that one or many of them will prove efficacious and modify the

course of the disease.”

Advancing programs

Although two Wave drug compounds failed in early-stage

trials, the company plans to start a trial of a third compound later this year.

Both Roche and Wave are scheduled to make the first scientific

presentations about their recent results this week at the greatly anticipated

16th Annual HD Therapeutics Conference,

April 27-29, a virtual event because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research

community is confident that a deep analysis of these studies will guide its

next steps in the quest for therapies.

Researchers and companies are investigating dozens of distinct designs

for the type of drug used by Roche and Wave, an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO).

Using surgery to inject its drug directly into the brain, Uniqure has started the first-ever HD gene therapy safety trial

in a small number of trial participants.

Triplet Therapeutics aims to start a Phase 1 clinical trial

in the second half of this year of a unique ASO targeted at stopping the mutant

huntingtin gene’s tendency for continued expansion with age (click here

to read more).

Genetic modification is not the only approach under study,

however. Several other firms have Phase 2 programs in the works to treat

symptoms and reduce disability due to HD,

and Neurocrine expects to complete KINECT-HD – its Phase 3 trial of

a chorea-reducing drug called valbenazine – by year’s end. Chorea is the

involuntary movements that afflict many people with HD. (On KINECT-HD, also click here.)

Two similar drugs for chorea – Xenazine

and Austedo

– are the only HD drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration

(FDA). They do not stop progression of the disease.

A big goal: helping HD people

function normally

A second major study, called PROOF-HD, is currently

underway, led by the Huntington Study Group

(HSG), and sponsored by Prilenia. This is a Phase 3 trial (the final step

before a drug can be approved by the FDA) of a drug called pridopidine, which

is proposed to improve function in people in the early stages of HD.

PROOF-HD stands for “PRidopidine

Outcome On Function In Huntington Disease.”

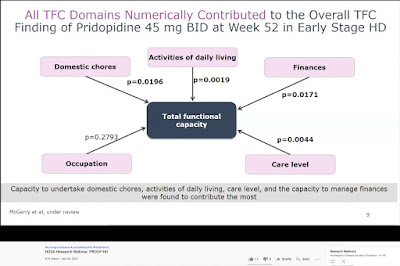

The

clinical trial investigators believe that, if tested successfully, pridopidine

would help early-stage HD-afflicted individuals maintain the ability to

function normally in five key areas: occupation/employment, managing personal

finances, performing household chores, performing activities of daily life

(such as bathing and dressing), and the ability to live in a home environment. These

five domains comprise the Shoulson-Fahn Total Functional Capacity Scale (TFC),

developed almost 40 years ago, and used daily in HD clinics and research

studies since then.

“The bigger the effect, the better,” Prilenia CEO Michael

Hayden, M.D., Ph.D., said in an April 1 interview about pridopidine with Evaluate

Vantage.

“But any significant change in TFC would be regarded as meaningful. There’s

never been a drug that has had any impact on TFC.”

Dr. Hayden is one of the world’s foremost HD scientists

(click here to watch our 2011 interview at

the Therapeutics Conference.) Prior to founding Prilenia in 2018, Dr. Hayden

served as the president of global R&D and chief scientific officer at Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd. from 2012-2017, where he

oversaw ongoing research on pridopidine. He is also a professor at the

University of British Columbia and a senior scientist at the Centre for Molecular Medicine and Therapeutics,

having mentored over 100 graduate students.

In a January 28 HDSA webinar,

Sandra Kostyk, M.D., Ph.D., a professor Ohio State University and the

co-principal investigator for PROOF-HD in the U.S., pointed out that

individuals’ Total Functional Capacity ranges from zero (severely reduced

function) to 13 (full function). In early and mid-early HD, people on average

lose about one point on the scale a year, she explained.

In later stages of the disease, TFC may be less reflective

of the rate of decline, Dr. Kostyk continued.

A slide from the January 2021 HDSA webinar on the PROOF-HD trial illustrating the Total Functional Capacity Scale and the effect of pridopidine (screenshot by Gene Veritas, aka Kenneth P. Serbin)

Stopping the house from burning down

As an HD gene carrier who saw his mother devastated by the

disease, I have most feared losing my ability to function normally.

In three previous clinical trials of pridopidine, carried

out between 2008 and 2018, both the original developer of the drug and Teva failed

to achieve the goal of reducing HD persons’ difficulties with both voluntary

and involuntary movements. At that time, scientists thought that pridopidine

affected levels of dopamine, an important chemical in the brain affecting

movements in both HD and Parkinson’s disease.

However, additional analysis (done

after the trials) showed that patients taking the study drug showed a slower

decline in TFC than expected from previous studies. “In early patients with

Huntington disease we have shown that the functional capacity may be maintained,”

Dr. Hayden observed in a January HSG podcast. “There also appears to be an

improvement and less deterioration in patients with early HD.”

Referring

to research conclusions published in the Journal of Huntington’s Disease

last December and co-authored by Dr. Hayden and five others, he asserted that the stabilized

TFC results were the “first time that this has ever been shown in any analysis

for any drug. This was exciting.” Significantly, the FDA accepts TFC

as a way of measuring drug efficacy in HD clinical trials, he added.

Those observations now require

confirmation in PROOF-HD, Dr. Hayden said.

Also, he continued, pridopidine “appears

to have beneficial effects around protecting neurons,” whatever the injury

might be. The goal, he said, is to prevent these brain cells from dying – one

of the major symptoms of HD.

“You want to treat them before

they've died,” he explained. “If you're trying to stop a fire taking care of a

house, you don't want the house to be burned down. And that's why treating early

becomes effective because there are still injured neurons, but not dead neurons.”

In

the HDSA webinar, Dr. Kostyk referred to pridopidine as a possible

“disease-modifying intervention –

something that slows the course of the disease.” The data indicate that

early-stage HD patients could obtain “long-term beneficial effects” from an

approved pridopidine drug for five years or more, she said.

That could buy valuable time for

older asymptomatic individuals like me and the HD community in general as we

await other gene-modifying or huntingtin-lowering drugs.

Prilenia: seeking to soothe the

impact of disease

Dr. Hayden explained the name and goals of Prilenia: “Prilenia, which comes from pri, as

in pridopidine, and lenia, which comes from the Greek, to sooth or to cure.

It's an aspiration that we can have some impact on soothing some aspects of

this disease and potentially others as well.”

Privately

held and based in Israel and the Netherlands, in 2020 Prilenia raised $68.5 million to

support PROOF-HD and also a Phase 2/3 trial in sufferers of amytrophic lateral

sclerosis (ALS).

The ALS trial is currently enrolling participants at 54 sites across the US.

Pridopidine taken as a pill

For HD sufferers, Pridopidine has another major advantage: whereas

ASOs so far have been injected into the spine and Uniqure’s drug has been

infused via brain surgery, pridopidine in the PROOF-HD trial is very

conveniently dosed in a 45-milligram pill – a hard gelatin capsule – taken

twice daily (click here for official details of the trial).

Pridopidine has been extensively studied in several previous

clinical trials over more than a decade, with more than 1,300 people taking the

drug, most of them with Huntington’s, Dr. Kostyk said. As a result, researchers

have high confidence in its safety, she added.

Other HD research projects and biopharmaceutical firms are

seeking so-called small molecule drugs that can enter cells easily and be taken as

a pill.

A key receptor in the brain

Dr. Hayden and his colleagues now believe that the benefits

of pridopine are due to its ability to activate the sigma-1 receptor (S1R). “It’s

highly selective and fairly potent,” Dr. Hayden explained about the action of

pridopidine on S1R in response to a question that I posed about the drug’s

basic mechanism during his presentation at the 27th Annual HSG Meeting (held

online) in October 2020.

Dr. Hayden observed further that ample data demonstrates

that activation of S1R leads to protection of neurons. Deficiencies in S1Rs

leads to disease. He cited the case of patients lacking the S1R gene, resulting

in juvenile onset ALS.

“The activation of the sigma-1

receptor has multiple mechanisms of action that should lead to neuroprotection

in HD and help stabilize cell function,” stated Dr. Kostyk, noting that S1Rs

are plentiful in the striatum – the inner core of the brain where HD is

especially devastating – and in the cortex, the large outer area of the brain

in charge of thought, language, and consciousness.

“One could think of the role of S1R

as being like that of a high school guidance counselor,” Martha Nance, M.D., director

of the HDSA Center of Excellence at Hennepin HealthCare in Minneapolis, MN, wrote

me in an e-mail. “When the receptor is turned on, materials, molecules, and

traffic within the cell flow as it should, and the cell stays healthy, much as

the counselor helps students in trouble to be safe, find resources to keep

healthy, and stay in school. Supporting S1R early in the course of HD might

help more brain cells to remain healthy and function well for longer.”

A relatively easy trial seeking

practical results

Initiated last October, PROOF-HD investigators hope to

enroll a total of 480 clinical trial volunteers by year’s end at 30 sites in

the U.S. and Canada and 30 more in Europe. Over 15 months, half will get

pridopidine, and half will get a placebo. Patients must have a diagnosis of HD,

be 25 or older (no upper age limit), and have a TFC score of at least 7, in

line with the project’s goal of testing the drug in the earlier stages of the

disease.

Participants will undergo measurements of their TFC, cognition,

quality of life, and motor symptoms (difficulties with voluntary and

involuntary movements). They will also get blood and safety tests. All

participants can take part in the potential extension of the trial, with

everybody receiving the drug. Dr. Kostyk described PROOF-HD as an “easy” trial,

with no brain scans or spinal taps (used in the Roche trial, for instance). The

study design has been adapted to accommodate the challenges posed by COVID-19.

PROOF-HD emphasizes practical results. “What’s most

important for us it to get an agent out that’s working,” Dr. Kostyk said, and

“not necessarily” the kinds of measurements used in other trials in order to

demonstrate how the drug works.

A separate trial might be designed later for later-stage

HD-afflicted individuals, Dr. Hayden said.

For more information on PROOF-HD, click here

or call 800-487-7671.

A potential major step forward

“Our overall goal is to get this

agent FDA-approved as soon as possible so that we can start using it in

individuals affected by Huntington’s disease,” said Dr. Kostyk. The more

quickly patients enroll in the study, the sooner it will be completed,

hopefully by late 2022 or early 2023.

Because this is a Phase 3 trial, if it is successful, the next step will

be an application to the FDA for approval as a drug that doctors can prescribe.

Andrew Feigin, M.D., the HSG chair and principal

investigator in the U.S. for PROOF-HD, said in the HDSA webinar that Prilenia

has also shown interest in a possible future trial involving pre-symptomatic

individuals like me.

Past skepticism about pridopidine

focused on the lack of hard evidence that the drug could really slow HD

progression (click here to read more). However, that

debate came before the discovery of a clearer picture of pridopidine as a

potential protector of neurons.

As will all clinical trials, the Huntington's community will be rooting for success in PROOF-HD. Although pridopidine may not cure HD, enabling people to have a few more years of normal daily function would be a major step in the quest to manage this complex disease.