In a new book about the broad issue of editing human DNA, a prominent biographer of scientific innovators proposes that such cutting-edge, potentially curative gene editing research prioritize Huntington’s disease.

“Our newfound ability to make edits to our genes raises some fascinating questions,” writes historian Walter Isaacson – author of studies of Leonardo da Vinci, Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein, and Benjamin Franklin – at the outset of his recently published The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race.

Code Breaker presents a crucial account of the biggest breakthrough in genetics since the discovery of DNA’s structure in 1953 by Francis Crick and James Watson.

Editing our DNA, the molecule that makes up our genes and guides our biological lives, to make us less susceptible to microbes like the coronavirus would be a “wonderful boon,” Isaacson suggests in the introduction.

“Should we use gene editing to eliminate dreaded disorders, such as Huntington’s, sickle-cell anemia, and cystic fibrosis?” he asks. “That sounds good, too.”

Jennifer Doudna, Ph.D., the subject of Code Breaker, has also embraced the concept of gene editing for HD if it can become a safe and effective therapy. Dr. Doudna won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her work in identifying and understanding the natural gene editing process now widely known as CRISPR, and the insight that this tool could potentially be refined for use not only in the laboratory, but ultimately also in the clinic, to alter human DNA.

x

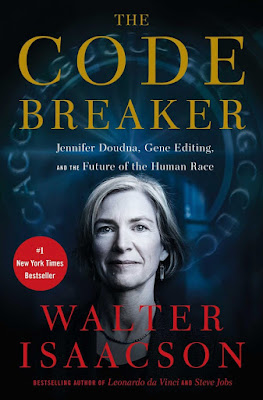

Above, author Walter Isaacson learns CRISPR editing, and, below, the cover of Code Breaker (images from Simon & Schuster website).

A historic breakthrough, major consequences

In Code Breaker, Isaacson traces the influence of the controversial Watson, now 93, on Dr. Doudna and others. He also interviewed Watson.

For both general readers and specialists, Code Breaker furnishes an excellent description of Dr. Doudna and others’ investigation of the structure and actions of CRISPR-Cas9, the specific type of gene editing feasible for use in humans.

CRISPR stands for “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats,” a strand of RNA, and Cas-9 for the enzyme associated with the RNA. Cas-9 acts as a type of scissors to cut DNA. The RNA guides the enzyme to the cutting target. There are other types of CRISPR.

Ultimately, Isaacson delves into the significance of CRISPR (and related themes such as biohacking and home genetic testing) for the future of humanity. CRISPR can perhaps end single-gene disorders like Huntington’s – but might ultimately also permit us to change such characteristics as IQ, muscle size and strength, and height. Russian President Vladimir Putin has extolled CRISPR as a potential way to produce “super-soldiers,” as Isaacson notes.

A powerful bioethical story

Isaacson has produced a powerful bioethical study of when and how gene editing should be done. He interviewed Dr. Doudna other scientists on their views. He also consulted bioethicists and their writings.

He also contrasts competing political theories regarding editing, pitting the idea of a free-market “genetic supermarket,” where the individual decides, against that of a society (and its government) that would permit editing only if it did not increase inequality.

Thus, Code Breaker is a major contribution to bioethics (the ethics of medical and biological research). Isaacson analyzes the potential social, moral, ethical, political, and ultimately biological consequences of gene editing and the conflicts it might produce. Editing the human race could produce many wonders, but also less biological diversity and greater and more permanent inequality, as the rich will almost inevitably gain privileged access to therapies and enhancements.

Isaacson illuminates this dilemma by recounting Dr. Doudna’s own “ethical journey” on gene editing.

“By limiting gene edits to those that are truly ‘medically necessary,’ she says, we can make it less likely that parents could seek to ‘enhance’ their children, which she feels is morally and socially wrong,” he writes. The lines between the different types of edits can be blurry.

“As long

as we are correcting genetic mutations by restoring the ‘normal’ version of the

gene – not inventing some wholly new enhancement not seen in the average human

genome – we’re likely to be on the safe side,” Dr. Doudna affirms.

Code Breaker also offers important evidence of the tension between so-called open science, where researchers (and some biohackers) freely share data, and the scientists, universities, and corporations that fight to establish patents and earn profits. (Click here for more on this development.)

Making the case for editing the HD mutation

Isaacson recounts how, in 2016, Dr. Doudna was especially moved by a visit at her workplace, the University of California, Berkeley, with a man from an HD family, who described to her how his father and grandfather had died of the disease, and that his three sisters, also diagnosed with the disorder, now “faced a slow, agonizing death.”

Putting Huntington’s first in a series of bioethical case studies, Isaacson underscores the crucial need for an HD CRISPR treatment, noting the disease’s devastating symptoms and rare, dominant genetic nature (inheriting the mutation from just one parent is sufficient for getting symptoms).

“If ever there was a case for editing a human gene, it would be for getting rid of the mutation that produces the cruel and painful killer known as Huntington’s disease,” Isaacson asserts.

Eliminating HD forever

For HD, Isaacson suggests a germline edit—removing the elongated piece of DNA in the huntingtin gene that causes HD in an embryo. A treatment done at this stage would restore the normal function of the HD gene in all the body cells, including that individual’s eggs or sperm. This genetic repair would then be inheritable, thus erasing HD forever from the future generations of the family.

Scientific protocol and governments have not yet approved such edits, though they have been done in animal subjects. As narrated in great detail in Code Breaker, a Chinese researcher did such an edit – to prevent AIDS – in twin babies in 2018, only to be punished by his country’s government and criticized as irresponsible by scientific colleagues. However, Dr. Doudna and other pioneers of CRISPR remain hopeful that safe, inheritable edits will become acceptable for at least some conditions.

Isaacson mentions two alternatives to germline editing that can eliminate HD from a family’s lineage. First, adoption. Second, preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), which involves in vitro fertilization using embryos screened for the mutation. PGD has been used in the HD community for about 20 years. Before PGD arrived, some families, like mine, have had our offspring tested in the womb. However, neither of these strategies have been used widely in the HD community by at-risk couples.

If it can be harnessed safely, to target only the abnormal HD gene, and delivered effectively to human cells, CRISPR could provide the all-out cure for Huntington’s long sought by science and so deeply hoped for by HD families.

Isaacson concludes, “it seems (at least to me) that Huntington’s is a genetic malady that we should eliminate from the human race.”

For now, don’t ‘hold your breath’ for an HD CRISPR therapy

Isaacson states that “fixing Huntington’s is not a complex edit,” but he does not elaborate further.

However, while leading HD scientists are eagerly using CRISPR as a research tool, the technique is far from ready as a therapy.

CRISPR was a key topic at the “Ask the Scientist … Anything” panel of the virtual 36th Annual Convention of the Huntington’s Disease Society ofAmerica (HDSA), held June 10-13. Noting that many in the HD community have inquired about CRISPR, HDSA Chief Scientific Officer George Yohrling, Ph.D., asked the panel to comment on its potential as a therapy.

“CRISPR is really an exciting tool,” said researcher Jeff Carroll, Ph.D., co-founder of the HDBuzz website and, like me, an HD gene carrier who lost his mother to the disease. “CRISPR allows us really for the first time to edit DNA itself in a very precise way, to make very precise cuts in the DNA of a cell or even in an intact organism.” He added: “scientists are using it like crazy” in lab experiments.

In his own HD-focused lab at Western Washington University, Dr. Carroll and his team have developed a line of experimental mice with cells containing enzymes (proteins that act as chemical catalysts) necessary for doing CRISPR edits, Dr. Carroll explained. Such enzymes do not normally occur in human cells, he added.

Using CRISPR, “we can mess with these mice’s genome [DNA] in ways that were unimaginable just a few years ago,” Dr. Carroll continued.

Dr. Jeff Carroll commenting on HD science at the virtual 2021 HDSA national convention (screenshot by Gene Veritas, aka Kenneth P. Serbin)

For an HD family, “the idea of cutting out the DNA and fixing it is very, very appealing and something we can do in animal models and [animal and human] cell lines in the lab already, and it looks really promising.”

However, Dr. Carroll offered a blunt assessment of the current state of research on CRISPR as an HD treatment.

“As an actual HD therapy, I’m less excited about CRISPR,” he said. “I think it’s many years away. Something based on it may someday help us, but you have to realize that these enzymes that you need to enact CRISPR are themselves giant proteins that actually originate from bacteria, and we have to put them into the cell.

“So, if you want to use CRISPR as a therapy for Huntington’s and we want to modify all the DNA in the whole brain, we have to get into every one of your 84 billion neurons and put a CRISPR factor in there and modify the DNA.”

As a result, “Huntington’s will not be the first disease treated with CRISPR,” Dr. Carroll concluded. “I wouldn’t hold your breath for it as a therapy for HD in the medium or short term.”

Currently, a possible better candidate for a CRISPR treatment would be a disease involving immune cells that could be removed from the body, edited, and then reintroduced into the individual, Dr. Carroll observed.

Elaborating on Dr. Carroll’s comments, Ed Wild, M.D., Ph.D., another speaker at the HDSA science panel and also a co-founder of HDBuzz, cited the example of a blood cancer as a possible early target for CRISPR.

He agreed with Dr. Carroll that an HD CRISPR treatment remains difficult at this time and underscored why: unlike parts of the body like blood cells or bone marrow, brain cells cannot be removed, treated, and reinserted or given replacements.

Further cautions

An August 2020 HDBuzz article also urged caution in the use of CRISPR for HD and other genetic diseases in the wake of three experiments with human embryos that resulted in “unintended changes in the genome.” These so-called “off-target” effects suggest that “CRISPR is less precise than previously thought,” the article stated. Like desired edits, the unwanted ones make permanent changes to the DNA.

Such unintended edits are “bad because our DNA code is a very precise set of instructions, which can be thought of like a cooking recipe,” the article explained. “If you rearranged the steps in a recipe or got rid of some of the ingredients the outcome would not be good!”

When CRISPR is used in an embryo, the mistaken edits would not only affect that individual, but could also be passed on to the next generation.

Clarifying some key points

As an HD advocate and family member who has tracked the research for two decades, I felt that Code Breaker could have gone into greater depth about HD science. Given all the valuable detail about Dr. Doudna’s and other scientists’ efforts to discover the workings of CRISPR, it would have been helpful to present some scenarios about how it might work in HD.

Code Breaker also states that in HD the “wild sequence of excess DNA serves no good purpose.” This is a confusing term, as so-called “wild” type DNA in this context usually means “normal” DNA. Isaacson might better have done better to avoid the use of this term, but instead to emphasize that the normal huntingtin gene is essential for life and brain cell stability, as HD research has demonstrated. Normal huntingtin is present in all humans without the mutation and even in those who have inherited a mutation from one parent, because the non-HD parent has passed on a normal copy of the gene.

The book could have further benefited from additional references to both the scientific and social significance of the disease as presented in works such as Dr. Thomas Bird’s Can You Help Me? Inside the Turbulent World of Huntington Disease. There was also no reference to the pathbreaking research on modifier genes, which can hasten or delay the onset of HD.

Contemplating the ‘gift’ of life

Citing the philosopher Michael Sandel, Isaacson points out that finding “ways to rig the natural lottery” of genetics could lead humanity to humbly appreciate the “gifted character of human powers and achievements. […] Our talents and powers are not wholly our own doing.”

Still, I agree with Isaacson that “few of us would regard Alzheimer’s or Huntington’s to be a result of giftedness.”

Even so, it’s important to recall that HD researchers continue to investigate the role of the huntingtin gene not only in the disease, but, in the words of one study, in intelligence and the “evolution of a superior human brain.”

Faced with the daunting challenges of the disease, many HD mutation carriers and affected individuals have also grown in unexpected ways. I, for one, consider myself a lucky man because of the richer life I have lived as a result of my family’s fight against Huntington’s.

In this new reality, advocating once again for our families

HD families like mine have lived on the frontier of bioethics, facing challenges such as genetic testing, prenatal testing, genetic discrimination, decisions on family planning, and many others.

Perhaps, as Code Breaker speculates, gene editing may someday be considered morally acceptable in the way that in vitro fertilization and PGD have come to be.

However, as seen in the case of abortion, the HD community does not have a monolithic bioethical stance (click here and here to read more).

It remains an open question as to whether the HD community would wholeheartedly embrace CRISPR as a therapy. Some might celebrate it as a cure, but others might see it as going against nature or even as a return to the era of eugenics in the early- to mid-20th century, when medical professionals advocated sterilization for HD-affected individuals. Taking a cue from the United States, the Nazis were said to have forcibly sterilized as many as 3,500 people affected by Huntington’s.

No book can offer a definitive answer to these ethical quandaries. Code Breaker provides us with at least some basic guideposts.

It will ultimately fall to HD-affected individuals and their families (and those families affected by other diseases) to navigate what could very soon become the new reality of gene editing – and, when necessary, to act as powerful advocates. To assist us in this journey, we will need ethically informed health professionals and patient organizations.