Ten years ago this month, I exited the “terrible and lonely Huntington’s disease closet” by publishing an essay on my plight and advocacy as an HD gene carrier in The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Fortunately, asymptomatic as I near 63, I continue to teach, research the history of the HD cause, and enjoy family milestones such as my gene-negative daughter Bianca’s graduation from college and my wife Regina’s and my 30th anniversary celebration – events that I feared HD would prevent me from appreciating.

As we approach Thanksgiving, my favorite holiday, I feel a profound gratitude to my family, friends, and colleagues at work and in the HD cause.

So I want to reflect on my journey since exiting the closet. I also want to report on new paths of research that could offer hope for what we in the HD community (and beyond) desperately await: effective therapies (treatments).

Becoming a more effective – and convincing – advocate

I started this blog in January 2005 under the pseudonym Gene Veritas. Having told my family’s story using my real name (Kenneth P. Serbin) in a widely read publication has enabled me to become a more effective – and convincing – advocate. I could now speak with full transparency about HD, provide an example for others still hiding in the closet, and build new partners in the fight to raise awareness and funds.

Before exiting the closet, I was sheepish about fundraising and other aspects of my advocacy, restricting my efforts to relatives and close friends who knew about my family’s struggles. After my exit, I became more self-assured.

In 2013, the Serbin Family Team in the annual Hope Walk of the Huntington’s Disease Society of America (HDSA) became the top fundraiser nationwide, taking in more than $16,000 in donations from dozens of generous supporters.

Collaborating with work colleagues

I most feared the consequences of revealing my story at my workplace, the University of San Diego (USD), because of concerns about discrimination. I knew HD gene carriers had been fired by their employers. My USD colleagues were shocked by my revelation.

However, those colleagues ultimately showed great solidarity. By advocating about HD at work, I attracted new allies, boosted awareness, and served as a bridge to resources for those facing HD (click here to read more).

My advocacy reached a milestone in May 2017, when I traveled with my family to Rome to help represent the U.S. HD community at HDdennomore: Pope Francis’ Special Audience with the Huntington’s Disease Community in Solidarity with South America. My trip was sponsored by several USD units, including the Frances G. Harpst Center for Catholic Thought and Culture, directed by Jeffrey Burns, Ph.D. Later that year, the center hosted a talk by me exploring the social, scientific, and religious meaning of this extraordinary the papal event.

Francis became the first world leader to recognize HD, declaring that it should be “hidden no more.”

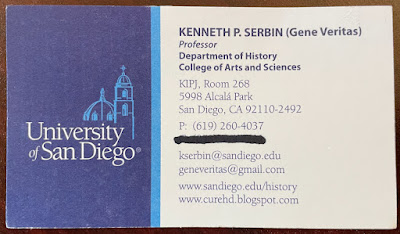

Business card of Kenneth P. Serbin (aka Gene Veritas) shared at scientific conferences and with anyone interested in learning about the HD cause (photo by Gene Veritas)

In early 2020, before the coronavirus pandemic exploded in the U.S., Dr. Burns and I collaborated in a screening at USD of the short documentary Dancing at the Vatican, which features HDdennomore. In late 2020 I helped promote the launch of the film online.

This year, I fulfilled one of the long-term goals outlined in my 2012 coming-out essay: shifting my academic focus from my beloved Brazil to the history of the quest for HD therapies.

With support from USD and The Griffin Foundation, I submitted the project for funding to the National Science Foundation. Although I was not granted funding initially, the foundation’s program officers encouraged me to reapply.

PTC’s helpful infusion of new capital

We all anxiously await effective therapies. Over the past ten years, I have increased my attention to the intensification of the efforts by labs and biopharma companies to achieve success.

The last several years of such efforts have felt like an emotional roller coaster for the HD community, though that’s not unusual for a difficult endeavor like drug development, which involves both positive and negative clinical trial results and cumulative learning.

Last month, I reported on the abrupt shutdown of the firm Triplet Therapeutics, Inc., which had explored a much-awaited proposed therapy. I also noted that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had requested that PTC Therapeutics, Inc., provide further information before allowing a clinical trial of its HD drug, PTC518.

But there was also potential good news.

Despite the FDA-imposed delay in a U.S. trial, PTC has reached a financing deal with the investment firm Blackstone, based on PTC’s plans to expand its drug pipelines to other diseases. The deal, which in the best-case scenario could infuse $1 billion of investment, puts “PTC in a strong position to continue to execute our mission,” Emily Hill, PTC’s chief financial officer, stated in an October 27 press release.

PTC518, a so-called splicing molecule, is also classified as a small molecule drug. It is thus taken as a pill – in contrast with riskier, less convenient delivery methods used by other HD programs, which include brain surgery and spinal injections. Early next year, PTC will furnish an update on the PTC518 trial. The trial continues in several European countries and Australia.

Roche diversifies its approach

In March 2021, Roche reported disappointing news: its gene silencing drug tominersen (an antisense oligonucleotide, or ASO) failed to improve symptoms in volunteers in the firm’s GENERATION HD1 Phase 3 (large-scale testing of effectiveness and safety) trial. This September, Roche announced GENERATION HD2, a less ambitious, Phase 2 (effectiveness, dosage, and safety) retesting of tominersen to start in early 2023.

In its presentation of GENERATION HD2 at the annual Huntington Study Group annual meeting in Tampa, FL, on November 3, Roche revealed that it has expanded its pursuit of HD therapies by embarking on two preclinical (nonhuman) projects.

Whereas tominersen targeted both the normal and abnormal (expanded) huntingtin gene, Roche will now seek to develop a drug that aims at just the abnormal gene. (Wave Life Sciences already reported in September that it had successfully targeted the abnormal gene in an early stage clinical trial, although yet without evidence of impacting symptoms.)

Like PTC’s program, Roche’s second preclinical program will aim at developing a splice modifier that would be taken orally.

“The medical need in the HD community is clear and we recognize that a range of different therapeutic approaches are likely to be required,” Mai-Lise Nguyen, of Roche’s Global Patient Partnership, Rare Diseases, wrote me in a November 3 e-mail.

A slide from the Roche presentation at the 2022 Huntington Study Group meeting illustrating the firm's three approaches to attacking Huntington's disease (slide courtesy of Roche)

Another ten years?

After the major disappointment in the shutdown of Triplet, I was heartened to learn of Blackstone’s massive investment in PTC, which indicates that both firms see PTC’s potential treatments as viable and profitable.

I was also encouraged to see how Roche, in the words of its Huntington Study Group presentation (see photo below), has augmented its HD research portfolio, reflecting a “commitment to advance scientific understanding and drug development in HD through continued collaborations” with HD organizations.

With the ingenuity of HD scientists and the dedication of HD family members to participation in research, the march towards potential therapies continues. I hope to chronicle continuing progress over the coming years not only free of the “HD closet,” but, thanks to new therapies, free of significant HD impacts, as well.

A slide from the Roche presentation demonstrating the commitment and collaborations involved in the quest for HD therapies (slide courtesy of Roche)