To

persevere against neurological diseases such as Huntington’s and the aging we

all face, I have learned that it is essential to develop meaning and purpose

and perform mental exercise.

In May

1997, just seventeen months after learning that my mother had the devastating symptoms

of Huntington’s, I confided for the first time in a medical professional who

was outside my local support group. Explaining my family’s predicament, I

revealed to a physician in Brazil, my second home,

that I had a 50-50 chance of having inherited the HD mutation.

Thomaz Gollop, M.D., an OB-GYN, knew about the harm

caused by genetic disorders such as HD and the enormous potential for psychological

trauma involved when a family learned it was at risk: in Brazil he helped

pioneer genetic counseling and testing, particularly for families who wanted to

conceive.

I had gone

to interview Dr. Gollop at his São Paulo clinic about abortion, a topic I was researching.

Though Brazil, a fervently Catholic country, had outlawed abortion, millions of

women found ways to terminate their pregnancies, often in precarious

circumstances.

The

disturbing history of this underground practice provides a cautionary tale for

the U.S. as our Supreme Court prepares in

June to apparently renounce five decades of protecting legal abortion. An

affiliate of the American Society of Human Genetics and member of the American

Association for the Advancement of Science, Dr. Gollop has been a leading

advocate in Brazil for women’s health and legalization of abortion, emphasizing

the medical – as opposed to religious – nature of the procedure.

I had not

yet tested for HD. Because of my risk, my Brazilian wife Regina and I had

postponed having children. I saw Dr. Gollop as a shoulder to lean on. I poured

out my heart about my mother’s struggles and my fear of becoming like her.

Dr. Gollop

told me: just keep doing what you like to do until the disease hits.

In my

journey of risk – I tested positive for the mutation in 1999, followed by our daughter

Bianca’s negative test in 2000 – I have frequently reflected on Dr. Gollop’s

advice by imagining the simultaneous challenge and beauty encountered by a

surfer riding a wave.

“Just keep

surfing through life!” I tell myself.

Celebrating our 30th anniversary in

Hawaii

During

this, Huntington’s Disease Awareness Month,

we must recognize the enormous caregiving and financial burdens imposed by HD.

As a result, affected families must often relinquish their dreams. Regina and I

did not have more children. We gave up buying a vacation condo in Brazil. I turned down an offer of a better job at a research university in another state so that, if I were

unable to work, we could rely on Regina’s secure salary and pension from her

job as a public school teacher.

My risk of

becoming disabled means we have focused on saving, to bolster my long-term care

insurance policy. So we usually take modest vacations.

This year,

though, we splurged a bit. To celebrate our 30th wedding anniversary – which I

had never expected to reach with the HD-free health I have enjoyed – we traveled to Hawaii for the

first time. In late March we visited the islands of Kona (the Big Island) and

Oahu.

We found

Hawaii wondrous with its primordial, balmy setting: we saw molten lava flow in

the crater of a volcano and heard a resounding chorus of birds sing at sunset.

Along with newlyweds and other couples marking anniversaries, we were called to

the stage at a luau to slow dance to a Hawaiian love song in celebration of “ohana,”

the Hawaiian word for family.

Keeping

alive the joy

I was

introduced to the story of the father of modern surfing, Duke Kahanamoku

(1890-1968), a native of the Waikiki neighborhood of Honolulu. A dark-skinned

man competing in a world dominated by white athletes and sports officials, Kahanamoku

impressed the world by winning gold and silver medals in swimming at the 1912, 1920,

and 1924 Olympics.

Also

active in rowing and water polo, Kahanamoku was one of the greatest athletes of

his era. Always around beaches and pools, throughout his life he also saved many

people from drowning.

I first

read about Kahanamoku in a guidebook praising the popular Honolulu restaurant that

he owned, Duke’s Waikiki. Powerful local interests had always

capitalized on Kahanamoku’s fame to promote Hawaii as a tourist mecca but

frequently abandoned him to struggle for economic stability on his own. He opened

Duke’s late in life as a way to supplement his income

Regina and

I visited Duke’s. It has Kahanamoku memorabilia, including one of his large

wooden surfboards. Outside the restaurant Regina took a picture of me in front of a giant wall photo

of Kahanamoku poised to take a dive.

Gene Veritas, aka Kenneth P. Serbin, standing in front of photo of Duke Kahanamoku in Honolulu (photo by Regina Serbin)

I was

intrigued by Kahanamoku. Returning home to San Diego, I wanted to keep alive

the joy I had felt in Hawaii. Exploring Hawaiian culture and history, I thought,

might build for me new dimensions of meaning and purpose.

Surfing

king Duke Kahanamoku and aloha

I delved

into journalist David Davis’ Waterman: The Life and Times of Duke Kahanamoku, the first comprehensive

biography of Kahanamoku (and the source of my observations here). By

coincidence, the moving documentary Waterman,

based on Davis’ book, premiered in theaters in April. I saw it on opening day.

In Hawaii Regina

and I were frequently greeted with “aloha,” and people used “mahalo” to say

“thank you.”

As an

official greeter of visiting dignitaries (including President John F. Kennedy)

and global ambassador for Hawaiian culture, Kahanamoku spent his life spreading

the spirit of aloha.

Davis

writes that Kahanamoku “suffused” visitors “with aloha because he believed that

promoting Hawaii was beneficial for fellow Hawaiians.”

Regina Serbin at Chief's Luau with flowers presented in celebration of our 30th wedding anniversary (photo by Gene Veritas)

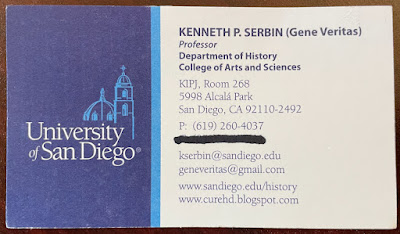

Kahanamoku

printed his personal philosophy on his business card:

In

Hawaii we greet friends, loved ones or strangers with ALOHA, which means with

love. ALOHA is the key word to the universal spirit of real hospitality, which

made Hawaii renowned as the world’s center of understanding and fellowship. Try

meeting or leaving people with aloha. You’ll be surprised by their reaction. I

believe it, and it is my creed.

(I have also

frequently encountered sincere hospitality in my years of traveling and residing in Brazil

and other Latin American countries.)

Although highly

competitive in athletic contests, Kahanamoku’s embodiment of aloha gained him a

reputation as a humble victor and cooperative teammate.

He refused

to respond to the many racist epithets he endured. He suppressed his feelings

when personally attacked or taken advantage of by others so much that he

developed ulcers.

Nevertheless,

with his athletic prowess and aloha, Kahanamoku entered areas of society

normally reserved for whites.

As Davis

observes, “Many years before nonwhite athletes like Joe Louis, Jesse Owens, and

Jackie Robinson fought racism with courageous performances, Kahanamoku was a

groundbreaking figure who was able to overcome – some would say transcend –

racism.”

The

wisdom of a waterman and his people

For Native

Hawaiians, Kahanamoku’s plight symbolized the unwanted but steamroller-like annexation

of the independent nation by the U.S. (in 1893); the adulteration of the

environment by settlers from the mainland; the imposition of mainland culture

and language on the locals; and, ultimately, the commercialization of society

in favor of tourism, plantation agriculture, and the establishment of Hawaii as

a major military installation.

In the

words of another fine documentary, Hawaii is a “stolen paradise.”

Not

surprisingly, Kahanamoku’s extended family retained no ownership in Duke’s

Waikiki, which expanded to include restaurants on two other Hawaiian islands

and also in three California coastal cities.

Despite

this history, Hawaii fortunately has maintained much of its connection to

nature and cultural traditions. With aloha and their intimate ties to the land

and water, Kahanamoku and his fellow Native Hawaiians (along with natives

elsewhere) offer a connection to premodern humanity and the importance of

solidarity.

That

spirit resonates with the fight for human well-being fundamental to the

Huntington’s cause. As I tweeted

in March, “Fortitude, collaboration of #HuntingtonsDisease movement embody

opposite of aggression of war in @Ukraine: caregiving, alleviation of

suffering, and harnessing of science for cures. #IStandWithUkraine.”

A

“waterman,” Kahanamoku felt most at home in the sea, the source of life and the

substance inhabiting our inner parts.

In a time

of global warming, political strife, and warfare, the world has much to learn

from the wisdom of aloha and Hawaiians’ immersion in nature.

Kenneth and Regina Serbin with Waikiki Beach and Diamond Head volcanic cone in the background (family photo)

Negotiating

the waves of life

Modern

surfing emerged from Hawaii. The greatest surfer of his time and global

popularizer of the activity, Kahanamoku did not see it as a sport. It was about

his love for, and relationship with, the sea. And about pure fun.

“The best

surfer out there is the one having the most fun,” he said. After World War II,

with the worldwide explosion in surf culture, competitions, and surfboard

technologies, Kahanamoku marveled at – and was deeply proud of – how it took

hold. He did want to see it included in the Olympics, which finally

occurred in the 2020 games.

I tried

surfing once in my 20s but did not pursue it. At 62 and still healthy, and with

the example of Kahanamoku, I have thought of perhaps trying again, if I can

find a patient instructor!

More

importantly, Dr. Gollop’s advice rings true: to stave off Huntington’s onset, I

need to keep doing what I like – including exploring Hawaiian culture and

history.

The

thought of Kahanamoku flawlessly negotiating the waves on his board also

reminds me of the need – with aloha – to find in life “the right balance between striving and chilling.”

This week

I am balancing my disappointment over a professional roadblock with the joyous celebration

of Bianca’s graduation from the University of Pennsylvania.

I hope that

those of us in the Huntington’s community and beyond can all learn to surf

through life like Duke Kahanamoku – and always with aloha.

Regina (left), Bianca, and Kenneth Serbin during graduation weekend at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia (family photo)