With the

U.S. Supreme Court’s radical toppling of long-standing abortion rights on June 24, families affected by Huntington’s disease and thousands of other rare and neurological disorders

face a profoundly uncertain future regarding medical care in the United States.

The majority opinion in the 5-4 decision overturned the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling, which was reaffirmed in the 1992 Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision. Those previous rulings guaranteed a woman’s right to an abortion before viability of the fetus.

Now, the authority to regulate abortion has been returned to Congress and the states. The court voted 6-3 in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, confirming a Mississippi ban on most abortions after fifteen weeks of pregnancy.

The majority position held that the Constitution does not confer a right to abortion.

Complicating a heart-wrenching situation

HD families have relied on prenatal genetic testing and abortion to prevent passing on the genetic mutation to their children. My mother died of HD in 2006, and I tested positive for the mutation in 1999.

In 2000, our gestating daughter tested negative for HD in the womb, forestalling the need for us to consider abortion. She just graduated from college.

Sadly, many families have lost children to juvenile HD (JHD).

Now, access to abortion will disappear or be severely restricted in almost two dozen states.

“This

complicates an already incredibly difficult and heart-wrenching situation for

women affected by HD,” leading

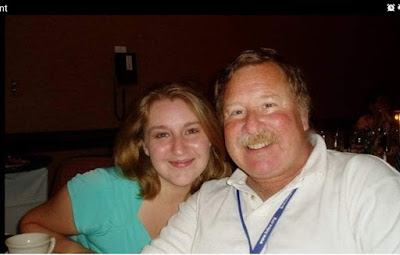

advocate Lauren Holder wrote me in a Facebook message regarding the abortion ruling. An HD gene

carrier, Holder has one at-risk child, and other who tested negative during the pregnancy. She lost her father Stephen Rose, Jr., 62, to HD last year.

“If I could recommend one thing, it would be to not let [our reaction] stand as just a sad or irate post on social media,” Holder urged. “If we want this to change, we have to be willing to speak up and advocate for ourselves, for women’s rights, at the state level now.”

Lauren Holder (left) with her late father Stephen Rose, Jr., who died of HD in 2021 (personal photo)

HD sheds light on bioethical challenges

As I reported in 2011 (click here and here), controversy over abortion in the HD community reflects the national societal divide.

However, confronting HD’s devastating symptoms and stigma, our community’s early and deep experience with genetic and prenatal testing, preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), suicide, assisted suicide, euthanasia, disability legislation, mistreatment by the police, a crushing caregiving burden, and other challenges have made us bioethical pioneers.

Those issues include human embryonic stem cell research, crucial for developing a greater understanding of HD and potential therapies. I commented on religious leaders’ concern about the research in a September 2017 presentation on Pope Francis’s historic meeting the previous May with the HD community in Rome, where he declared HD to be “hidden no more.” My family and I attended.

Francis had encouraged the HD scientists present to avoid research involving human embryos, “inevitably causing their destruction.”

“Bioethicists, both within and without the [Catholic] Church, can learn from the HD community,” I asserted. “This is not an easy issue, but it requires dialogue. Unfortunately, some media outlets focused on this aspect of the meeting, ignoring the historic moment and how Francis exuded love towards us in the HD community.”

Defenders of the sanctity of human embryos continue to support a ban on this research.

Some abortion opponents have also proposed that embryos have legal status as persons.

PGD in jeopardy?

The blistering Supreme Court dissenting opinion by the three liberal justices described the decision as “catastrophic,” taking away women’s freedoms, threatening other rights, and eroding the court’s credibility.

Because of the majority’s position, the dissenting justices affirmed that the Supreme Court will “surely face critical questions” about how the ruling will be implemented.

“Further, the Court may face questions about the application of abortion regulations to medical care most people view as quite different from abortion,” the dissenting justices wrote. “What about the morning-after pill? IUDs? In vitro fertilization?”

Earlier this month, in anticipation of the expected overturn of the right to abortion, HD advocate Allie LaForce recognized that changes in the laws in some states might lead her and her untested, at-risk husband, Minnesota Twins baseball pitcher Joe Smith, to change their approach to assisting families with PGD through their foundation, HelpCureHD. PGD involves in vitro fertilization. LaForce is currently pregnant after using PGD.

LaForce and Smith have considered the possibility of paying for families to travel out of state for PGD if they live in a place that has restricted the practice. The extra cost might reduce the number of families HelpCureHD can help.

A cautionary tale from Brazil

Previously, I noted my long study of the disturbing history of abortion in Brazil, where it is illegal except in cases of rape and incest, danger to the life of the mother, and anencephaly, a fatal condition in which a fetus lacks a complete brain.

Each year, hundreds of thousands of women are hospitalized in Brazil because of complications of illegal abortions, and, overall, thousands have died. This tragedy provides a stark warning for the U.S. as it attempts to adjust to the Supreme Court decision.

I wholeheartedly agree with the emphasis on the medical – as opposed to religious – nature of the abortion question. I also believe in a woman and her family’s right to choose. In Brazil, I carefully studied – and came to identify with many of the ideas of – the local version of Catholics for a Free Choice.

The Supreme Court does not consider letters from the general public in its decisions. In April, I had begun exploring how to contribute to an amicus brief, which can only be filed by individuals or organizations registered with the court. I hoped to send a copy of an article I had published in 1995 in The Christian Century on abortion in Brazil as well as copies my blog articles on HD, abortion, and bioethics.

The stunning May 2 leak of the court’s draft majority decision made any potential input a moot point. The final version largely tracked the draft.

Respecting individual decisions

In the late 1990s, during a conversation about abortion with one group of poor women in a Rio de Janeiro slum, they told me: “cada caso é um caso,” that is, each woman’s situation is different.

After my 2011 articles on HD and abortion in the U.S., I came to that same conclusion after reflecting on the contrasting predicaments of the couple who aborted their gene-positive child and the 20-year-old JHD-affected woman who decided to have her untested, at-risk baby.

In the immediate aftermath of the news of the abortion decision, I was struck by the comments of Phil Metzger, the lead pastor of Calvary San Diego, a local Christian church

“My reaction is mixed, which you might not expect to hear from a pastor of a church,” Metzger said in a radio interview. While the decision was a victory for abortion opponents, it was also a moment to remember those struggling with the reversal of Roe v. Wade, he observed.

“Every place, I don’t care what institution it is, statistically, somebody in that group had an abortion,” Metzger continued. “So we have to ask ourselves, ‘Are they my enemy?’ They're not. And whatever reason brought them to making these hard choices, God loves them.”

Metzger’s words echo the middle ground sought by some in the abortion debate but drowned out by the fierce political and legal battles.

Sadly, the “hard choices” just got immeasurably harder for many women, especially those disadvantaged by poverty and, now, distance from the states where abortion will remain legal for at least the time being.