Triplet

Therapeutics, Inc., a Cambridge, MA-based start-up that aimed to transform the treatment of Huntington’s disease and related disorders,

has shut down, citing a lack of new investment

partners and the discovery that its proposed HD drug caused adverse effects in

animal tests.

On October

11, Triplet CEO Nessan Bermingham announced the company’s closure on his

LinkedIn page. The abrupt closure was another

piece of tough news regarding potential therapies for HD.

In March

2021, Roche and Wave reported negative trial results for drugs aimed at reducing the

toxic mutant huntingtin protein in patients’ brains. These drugs are antisense

oligonucleotides (ASO), a synthetic modified single strand of DNA that can

alter production of certain proteins.

Triplet’s

strategy

Triplet

had designed its own ASO, but with a different strategy: to stop the

deleterious expansion of the mutant huntingtin gene (click here to read more). Known

as somatic expansion, this process drives the disease and can hasten the onset

of symptoms. By slowing this expansion, Triplet had hoped that its drug would head

off the disease early.

Triplet

scientists and others have viewed this approach as a more effective alternative

to the “huntingtin lowering” strategy devised by Wave, Roche, and others.

Capitalizing

on recent groundbreaking HD genetics research, Triplet, founded in late 2018,

developed the only clinical trial program to slow or stop somatic expansion in

HD. Triplet also had hoped to develop treatments for others among the 50 rare

conditions with somatic expansion, which, like HD, are called repeat expansion

disorders.

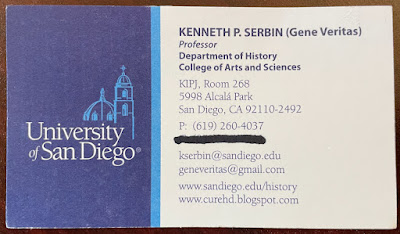

Brian Bettencourt, Ph.D., Triplet's former senior vice president for research, explains a slide illustrating the firm's pathway to a potential HD drug at the 15th Annual HD Therapeutics Conference, 2020 (photo by Gene Veritas, aka Kenneth P. Serbin).

“It is

with great sadness we announce the closure of Triplet Therapeutics,” Bermingham

wrote on LinkedIn.

The

“underlying science of targeting repeat expansion disorders” remains “a viable

approach from our vantage point,” Bermingham wrote. However, crucially, in

animal studies, the data from Triplet’s HD drug “reflected prior experiences”

with ASO toxicity in the central nervous system – a reference to the Roche and

Wave results.

Specifically,

the ASO showed signs of harming neurons (brain cells). “As a therapeutic

modality, given Roche’s data, our data, lack of efficacy from Wave products,

our belief is that neurons may be particularly sensitive to antisense

oligonucleotides,” Bermingham told STAT.

Triplet

secured $59 million in initial financing and investment. After the bad news in

2021 from Roche and Wave, Triplet struggled to raise the money needed for its

planned next step: an early phase clinical trial of its ASO. “The clinical data

really put a chill on the overall interest or risk perceived within

Huntington’s disease,” Bermingham noted.

SHIELD HD

continues to provide key data

To provide

data about the disease for the clinical trial it was planning, Triplet has run

a separate, two-year study, without a drug, of approximately 70 presymptomatic and

early-disease-stage carriers of the HD mutation. Called SHIELD HD, the study involves cognitive

testing, brain MRI scans, blood tests, and examination of cerebrospinal fluid

drawn from spinal taps (click here to read more). The sites are Canada,

France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the U.S.

In March,

Triplet scientists presented a preliminary analysis

of this data at the 17th Annual HD Therapeutics Conference, sponsored by CHDI Foundation, Inc., the virtual nonprofit

biotech focused exclusively on developing HD therapies. CHDI is the largest

private funder of HD research.

SHIELD HD may end in the next few months. In Bermingham’s announcement about the closure

of Triplet, he said that CHDI, “a great partner and patient advocate,” stepped

in to help SHIELD HD sites complete their work.

Triplet’s

representatives are now seeking potential partners to continue the company’s

research, including a new plan for a clinical trial.

Assessing

risk

In an online

interview with me on October 21, Irina Antonijevic, M.D., Ph.D., the former

chief medical officer of Triplet, explained that discovering toxicity of the

ASO in the animal studies surprised the firm’s researchers. However, she

emphasized that the toxicity was “minimal” at therapeutic dose levels, with the animals not suffering any

functional loss.

As noted

publicly, Triplet had also developed several, more potent backup ASOs, Dr.

Antonijevic said. The more potent the drug, the smaller the dose needed,

therefore reducing the chance of toxicity or an adverse effect, she added.

Nevertheless,

in a more risk-averse investment climate, Triplet could not find the necessary

partners to carry on its clinical trial program with the added concern about the

toxicity, Dr. Antonijevic observed.

“I think

that they are just sort of very different risks,” she said. “Somebody takes

maybe a risk to say, ‘Maybe this drug has a risk, but I have a disease, and I

know what this disease will do to me.’”

For a drug

company, the risk involves “investing millions” and waiting years to see if there is a return on investment, she said.

Tweaking

drug safety, efficacy, and delivery

Triplet’s

experience revealed how the field of HD drug development needs to tweak the

safety, efficacy, and delivery of ASOs into the brain. Despite the challenges,

a number of other firms and many researchers believe ASOs merit more study and

clinical trials.

Roche has

developed a revised clinical trial plan, including lower and thus potentially

less toxic doses of its ASO. It will start a second trial of that ASO in early 2023.

Wave, building

on its failed 2021 early stage trials of two ASOs, put a third drug into another

small, early phase trial. Unlike the previous drugs, this Wave ASO successfully

reduced the mutant huntingtin protein. Also, for the first time, it did this without

lowering the level of the healthy protein – something that occurs with the

Roche drug.

“This is,

as far as we know, the first time anyone has ever selectively lowered only one

copy [of a total of two] of a protein inside of a human body,” the HD science

site HDBuzz commented on Sept. 30.

The method

of delivery is important for all drugs, especially for ones introduced into the

brain. The Roche and Wave trials use spinal taps (intrathecal injections).

Triplet had projected using an

injection

via a small reservoir implanted on the top of the brain. The firm uniQure is

injecting its drug using brain operations.

Developing

a pill

Drug

developers point out that the most convenient HD drug would be a pill – taken

orally, at home, and without medical assistance. These drugs are known as small

molecules.

Several

firms have embarked on small molecule clinical trial programs for HD.

An

important trial of one of these small molecule drugs, a huntingtin-lowering

pill developed by Novartis, was halted in

August for safety reasons. Some of the trial volunteers on

the drug developed problems with their nerves, known as peripheral neuropathy.

FDA

requests more data from PTC

On October

18, another firm enrolling people in a clinical trial for a small molecule, PTC Therapeutics, Inc., was asked by the U.S. Food and

Drug Administration (FDA), to provide further information

before allowing a clinical trial of its HD drug, PTC518. PTC announced that

enrollment is ongoing for the planned 12-month Phase 2 trial in several

European countries and Australia.

Both

branaplam and PTC518 are so-called splicing molecules.

“PTC

pioneered the development of splicing molecules and we have learned about the

essential elements to successfully develop these molecules,” Jeanine Clemente,

the senior director of corporate communications at PTC, wrote me in an October 20 e-mail

in response to my questions about the FDA decision. “We cannot comment on the

FDA’s thoughts regarding branaplam or splicing molecules, in general.”

However,

Clemente pointed out that PTC518 is highly specific and selective for the

huntington gene.” She added that, in many important ways, “PTC518 is different

than branaplam.”

HDBuzz

also noted

that PTC518 “may have more ideal drug properties, compared to branaplam.”

The FDA has asked PTC for additional data to support

the dose levels and duration proposed in the trial, Clemente wrote.

Clemente added that PTC enrolled its trial entirely with

patients outside of the U.S., including approvals to conduct the study at all

proposed dose levels. “There have been no treatment-associated adverse events

reported to date,” she stated. “We will continue to work with the FDA to

potentially enable enrollment of U.S. patients in the trial.”

Keeping

perspective in a difficult fight

Triplet

will host a podcast later this year to discuss the “birth, life and death” of

the firm, CEO Bermingham stated in his announcement of the closure.

The HD

community must keep the Triplet shutdown – and all news regarding the ups and

downs of the search for HD therapies – in perspective, noted Martha Nance,

M.D., the director of the Huntington’s Disease Society of America Center of

Excellence at Hennepin County Medical Center in Minneapolis.

“We would

not do research if we already knew all the answers,” Dr. Nance wrote me in

an October 18 e-mail. “HD patients and families have bravely faced their

difficult disease for generations, and the doctors and scientists are doing

their best, along with patients and families, to find a brighter path.”

As an asymptomatic

HD gene expansion carrier who has not yet participated in a clinical trial, I

had high hopes for the Triplet program, with its focus on attacking the disease

in the early stages. I was deeply saddened to hear that the firm closed. I also

felt in the gut once again the hard reality of marshalling resources –

including financial support – for combating rare diseases.

Companies

like Triplet are venture capital-funded businesses pursuing high-risk,

high-reward endeavors, and many such endeavors fail. So we are fortunate to

have a nonprofit like CHDI as a backstop.

Dr.

Nance’s wisdom reminded me of the need to join with my fellow HD and rare

disease advocates to regroup in the fight for therapies.

“Finding a

solution to brain cell death in HD is not easy,” she observed. “And as we edge

closer to an answer, each failure seems more dramatic. It would be nice if the

answer would just reveal itself, if the answer to HD was simple and easy, but

we will not let the setbacks of the last two years prevent us from moving

forward.”